July 2025

July 2025

Real assets don’t create value just by existing. Yet for much of the past two decades, investors behaved as if they did.

From infrastructure to forestry and farmland, real assets were treated as bond proxies. In a world of near-zero rates, they offered stable, inflation-linked returns and long-duration characteristics that suited institutional portfolios. This period also marked the arrival of large-scale institutional capital into these sectors. Simply being early was enough. First movers benefitted from a general uplift in valuations as capital flowed in, even without active management or operational improvement.

That era is over. With interest rates lowering and capital more selective, real assets must now do more than passively deliver income. Like private equity, they must create value. Exposure alone is no longer sufficient.

Nowhere is this shift more evident than in infrastructure and natural capital. These sectors were historically underwritten on the basis of long-term leases, government guarantees or assumed land appreciation. But return expectations have changed. Delivering 10 percent-plus net returns now requires active oversight and operational intensity. Investors also want to see tangible cash yield and realised performance, not just long-dated projections.

This is not a call to retreat from real assets. Quite the opposite.

These investments remain essential: resilient, inflation-linked and central to long-term structural themes such as decarbonisation, food security and climate adaptation. But to justify their place in future portfolios, they must evolve from passive exposures to platforms for growth.

That means adopting the tools and mindset of private equity, including forward integration, margin expansion, consolidation and active risk management. It also means moving away from reliance on external project developers. That model, often characterised by layered fees and misaligned incentives, has come under pressure. In today’s environment, investors are looking for aligned, agile managers who can operate with speed, focus and control.

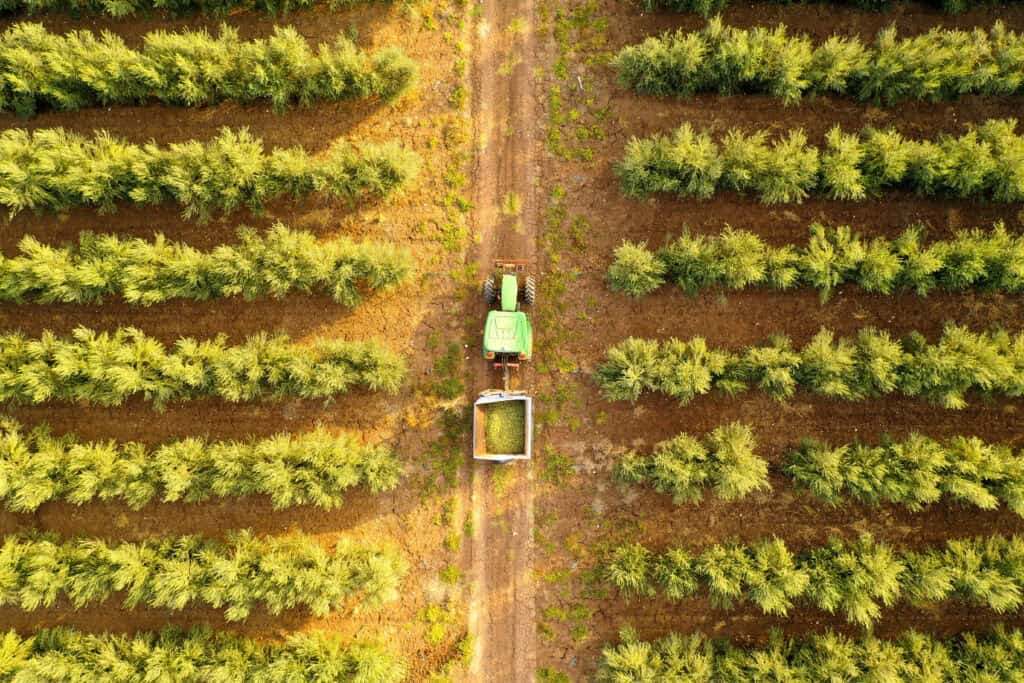

In agriculture, this might involve integrating farming operations with land ownership, packing and processing. In forestry, it could mean monetising environmental assets such as carbon or biodiversity credits, and optimising land use to reflect both ecological and commercial value, including renewable energy potential.

Infrastructure is undergoing a similar transformation. Investors are increasingly backing platforms that control both the operating company and the asset base, in sectors such as fibre, data centres and district heating. This allows them to capture value from both operations and underlying asset growth. Ancillary revenues, once overlooked, are becoming key contributors to performance.

Some of the world’s largest pension funds are already moving in this direction. Institutions such as PSP Investments, CDPQ and APG are deploying capital directly into businesses and platforms, taking a more active role in shaping returns. Other allocators will follow. But unlike these giants, most lack the internal scale or capability to execute directly. They will need specialist, entrepreneurial managers to deliver value on their behalf.

This raises an uncomfortable question for many incumbent managers: can they adapt? Their scale, overheads and centralised operating models resemble legacy financial institutions. Often slow, costly and inflexible, they risk being left behind. It is more likely that the next wave of real asset alpha will be delivered by smaller, more dynamic managers that are built for speed, integration and operational execution.

This model demands strong governance, corporate agility, operational capability and long-term thinking. But the reward is not just enhanced return potential. It also offers greater alignment, resilience and control.

The message is clear. Passive ownership may still have a place in core portfolios, but it is no longer a reliable engine of performance. In a higher-rate, capital-disciplined world, real assets must behave like businesses: actively managed, operationally led and strategically aligned.

The next era of outperformance will not come from where capital is allocated, but from what is done with it.

Author

|

|

| Eoin McDonald Director, Global Natural Capital |

Gresham House

Specialist asset management

Gresham House

Specialist asset management