What is natural capital?

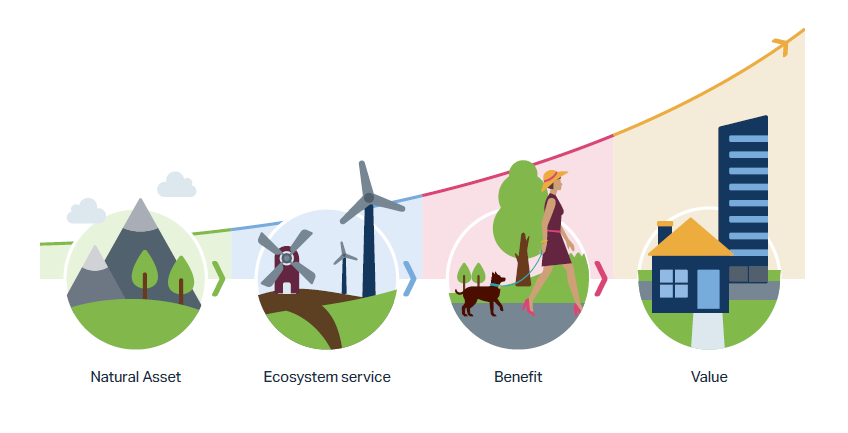

Natural capital is defined by the Natural Capital Coalition as the stock of renewable and non-renewable natural resources that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people and planet. These benefits are commonly known as ecosystem services.

Renewable natural resources can regrow or renew, such as plants, animals, air and water.

Non-renewable natural resources are finite and non-living, such as fossil fuels, soils and minerals.

How is biodiversity related to natural capital?

Biodiversity is defined as the variability among living organisms from all sources, including terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems1.

It is an essential characteristic of nature and is critical to maintaining the quality, resilience, and quantity of ecosystems2. The provision of the ecosystem services on which business and society rely are underpinned by biodiversity and without it many ecosystem services will fail.

Biodiversity loss poses an existential threat to human survival and prosperity which must be addressed within all aspects of our economies and financial systems.

What is the role of natural capital in the global economy?

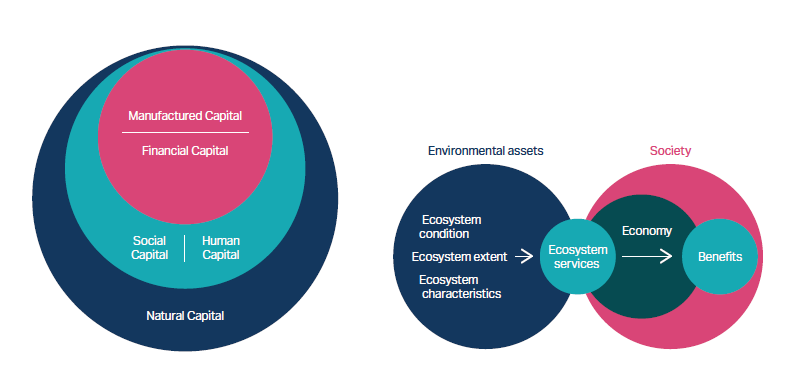

In economic systems we need to value all types of capital. Humans are in the most part paid a salary, placing a value on human capital. The products and services we consume are rarely free, placing a value on produced capital. The third capital component of our economies is natural capital.

All economic activity relies on natural capital. From creating the conditions to support life on earth to producing the raw materials used in the products we consume, the global economy would not exist without nature.

Despite this fundamental role, natural capital has not been recognised as an economic asset in the same way as human or produced capital for example. If the contributions of natural capital to the global economy were to be valued in the same way as other types of capital, it would have an estimated value of $125tn, equivalent to 1.25x Global GDP in 20223.

What is the state of nature today?

Today, we consume the equivalent of 1.6 Earths just to maintain our current way of life4. This has led to 75% of the Earth’s land surface being significantly altered by human activity5, with just 3% of terrestrial ecosystems still ecologically intact6. Wild populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish have dropped on average 69% in the last 50 years7.

Since 1990, the planet has lost 420 million hectares of forest through deforestation; this is not only harmful for biodiversity, but also contributes between 12-20% of global GHG emissions 8,9.

The UK in particular is one of the most nature depleted countries, with more than half of its biodiversity lost through human activity since the industrial revolution10.

What is causing the loss in nature?

The five main drivers of nature loss are: land use change, climate change, resource extraction, pollution, and invasive alien species11.

The global food system is the primary driver of biodiversity loss with agriculture alone threatening 86%12 of species at risk of extinction. However, sacrificing nature to meet increasing food demand has now put $577 billion13 in annual crop production at risk due to the loss of pollinator species.

Despite the worsening state of nature, around $7 trillion is invested globally each year in activities which have a direct negative impact on nature14. This includes private financing of industries such as construction, electric utilities, real estate, oil and gas, and food and tobacco. These industries in aggregate represent 16% of investment flows in the global economy but represent 43% of all nature-negative flows.

As well as this, government subsidies for agriculture, fossil fuels, fishery, and forestry that focus solely on economic output and drive unsustainable practices totalled $1.7 trillion in 202215.

How are nature and climate change linked?

Losses to nature are being accelerated as global temperatures increase. Even if global temperature increases are limited to 2˚C, 8% of the world’s mammals will lose their habitats16 .

Climate change is one of the key causes of nature loss but we need nature and biodiversity to avoid the worst affects of climate change. The two topics are inherently linked and cannot be considered in isolation.

Nature is a crucial ally in our ambitions to limit global temperature increases and avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Over the past 10 years nature has absorbed 54% of man-made carbon emissions in our land and our oceans, with the remaining 46% of emissions accumulating in the atmosphere, contributing to climate change17.

The combination of emissions continuing to increase and nature being increasingly destroyed is deadly. Nature is our greatest ally in the fight against climate change, and it’s loss from our planet our greatest threat.

What is the biodiversity finance gap?

Just $64 billion was invested in nature-based solutions in 202218. Global investment in nature needs to increase at least four-fold, equivalent to $536 billion a year, to adequately address the climate, biodiversity and land degradation crises19, this is known as the biodiversity finance gap.

Closing the biodiversity finance gap is crucial for our societies and economies future prosperity. For every $1 invested in nature restoration, up to $30 of economic benefits are generated through the better provisioning of ecosystem services.20

Can you invest in biodiversity today?

In the last five years, a combination of regulation and voluntary frameworks have created tailwinds for delivering biodiversity as a new nature market commanding economic returns. The introduction of mandatory biodiversity net gain for planning permissions in England from February 2024, has created a catalyst for biodiversity as an investment class with biodiversity credits now sold in compliance and voluntary markets.

What are some examples of natural capital investments?

Natural capital investments and investment themes cover a wide and diverse range of activities. Examples include sustainable, productive forestry including afforestation and reforestation, sustainable agriculture, nature restoration including biodiversity net gain units (BNGs), sustainable urban infrastructure, waste management, carbon sequestration, improving water quality, improving air quality, peatland protection and restoration, wetland protection and restoration, marine / coastal regeneration, and watercourse, protection and restoration.

How can we transition from a nature-harming to a nature-positive economy?

It is estimated that the world’s natural capital could be worth as much as $125 trillion but nature markets today are only valued at just under $10 trillion21 .This highlights that nature’s true value is not accurately reflected in our current economic and financial systems.

Our failing to value nature, has led to its degradation. Putting a value on nature is complicated, but by doing so, market participants can be incentivised to;

1. Avoid causing further damage to nature

2. Reduce unavoidable impacts on nature

3. Take action to restore and regenerate nature.

Taking these three actions across our global economies should aid in the transition to a nature-positive economy.

Moving to nature-positive models could create annual business opportunities worth $10 trillion by 2030, as well as creating nearly $700 billion in savings annually through reduced operating costs22.

Investors will need to take precautions to ensure that their natural capital allocations and wider investment portfolios are driving positive outcomes and not adding to the $7 trillion of nature-negative flows, as many existing nature-market opportunities in agriculture, forestry, and fishing are driving nature loss.

How is the nature crisis being addressed in the global sustainability agenda?

A major milestone in the transition to a nature-positive economy occurred at the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 15), with the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). This global agreement sets out 4 goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030, with the headline ambition “30×30” – to conserve, restore and protect 30% of land and oceans by 2030.

Within this ambition is a goal to mobilise $200 billion per year by 2030 for investment in biodiversity, and a goal to progressively reduce harmful subsidies by at least $500 billion per year to 2030.

Prior to this, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set goals 14 (Life Below Water) and 15 (Life on Land) to directly address the degradation of nature.

The Taskforce for Nature Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) is an international initiative formed to develop nature-related disclosures so that organisations can provide clarity to investors, consumers and other stakeholders on where they have an interface with nature and what the nature related risks and opportunities faced by the business are.

The Capitals Coalition is another organisation that has formed to support businesses, financial institutions and governments by providing guidance on how to take a natural capital approach and include the true value of natural capital in decision-making.

What is the status of nature markets today?

Nature markets are where nature-specific revenues are generated as an integral part of the trade; these are estimated to be worth around $9.8 trillion today23.The majority of this is driven by commodity production, including agriculture.

Only a fraction of current nature markets are verified with sustainability certifications24. Hence investors allocating to natural capital through existing nature markets need to be careful to ensure their capital is not causing nature destructive outcomes.

Credit based markets and conservation markets are a growing focus for natural capital investors, however these markets currently represent just 1% of the value of all goods and services traded in nature markets25.

Examples of a credit based market – Carbon forestry

Carbon forestry is a developing natural capital market which places a value on carbon sequestration in forest biomass to generate carbon credits. Well executed afforestation projects can contribute to the atmospheric carbon removals required to stabilise global temperatures and create important co-benefits for local biodiversity and ecosystem integrity.

What could future nature markets look like?

Research from McKinsey suggests that nature markets such as credit, insurance and sustainability linked bonds will grow in demand, driven by climate change and consumer preferences. Nature specific credits and payments for ecosystem services are also gaining traction but supply of these solutions are relatively low but are expected to grow as corporates and governments become more aware of how their activities negatively impact nature.

Going forward nature markets need to align themselves to nature positive outcomes to ensure our global prosperity. This can be achieved through valuing nature as part of our economic and financial systems. The challenge arises in ensuring that the valuation methodologies are consistent across different assets and regions.

Payments for ecosystem services are another innovative market-based mechanism where beneficiaries, or users, of ecosystem services provide payment to the stewards, or providers, of ecosystem services. The income is then spent on management and conservation of the ecosystem to guarantee a flow of ecosystem services over-and-above what would otherwise be provided in the absence of payment.

What makes Gresham House well positioned for investing in natural capital?

Gresham House is the ninth largest natural capital manager globally and is investing in an increasing range of scalable and profitable natural capital assets26.

We provide our clients with a platform of return-generating natural capital assets with established track records, including sustainable forestry, sustainable agriculture, carbon forestry and biodiversity creation. Each asset has different risk and return profiles and outcomes for nature. We work with our clients to provide access to these options to create their natural capital portfolios which promote the transition towards a more sustainable economy.

We support the promotion of high standards throughout the whole Natural Capital market, for example:

- Gresham House is a co-founder of the International Sustainable Forestry Coalition which aims to achieve greater recognition of the importance of sustainable management and preservation of global forests in the fight against climate change

- We are investigating how we can collaborate with other investors to create a standardised approach to monitoring and reporting on the generation of carbon credits from certain forestry projects.

- Rebecca Craddock-Taylor is a part of a biodiversity working group at the Institute & Faculty of Actuaries to ensure actuarial advisers can guide their stakeholders on why natural capital is critical to risk management and investment strategies.

- UN 1992

- Taskforce for Nature Related Financial Disclosures

- WWF Living Planet Report 2018: Aiming Higher

- Becoming Generation Restoration, UNEP

- IPBES

- Where Might We Find Ecologically Intact Communities?

- WWF Living Planet Report

- Deforestation has slowed down but still remains a concern, new UN report reveals

- Climate Finance Thematic Briefing: REDD+ Finance

- State of Nature report

- TNFD

- Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), April 2021

- UN Environment Programme – Facts about the nature crisis

- State of Finance for Nature 2023

- UN State of Finance for Nature 2023

- UN

- Our climate’s secret ally: Uncovering the story of nature in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

- UN State of Finance for Nature 2024

- State of Finance for Nature 2023

- Beyond GDP: making nature count in the shift to sustainability

- Taskforce on Nature Markets, McKinsey

- New Nature Economy Report II: The Future of Nature and Business

- Global Nature Markets Landscaping Study

- Mckinsey, State of Nature Markets Today & Tomorrow

- Global Nature Markets Landscaping Study

- IPE February 2024

Gresham House

Specialist asset management

Gresham House

Specialist asset management