Monthly Monitor - November 2023

Monthly Monitor - November 2023

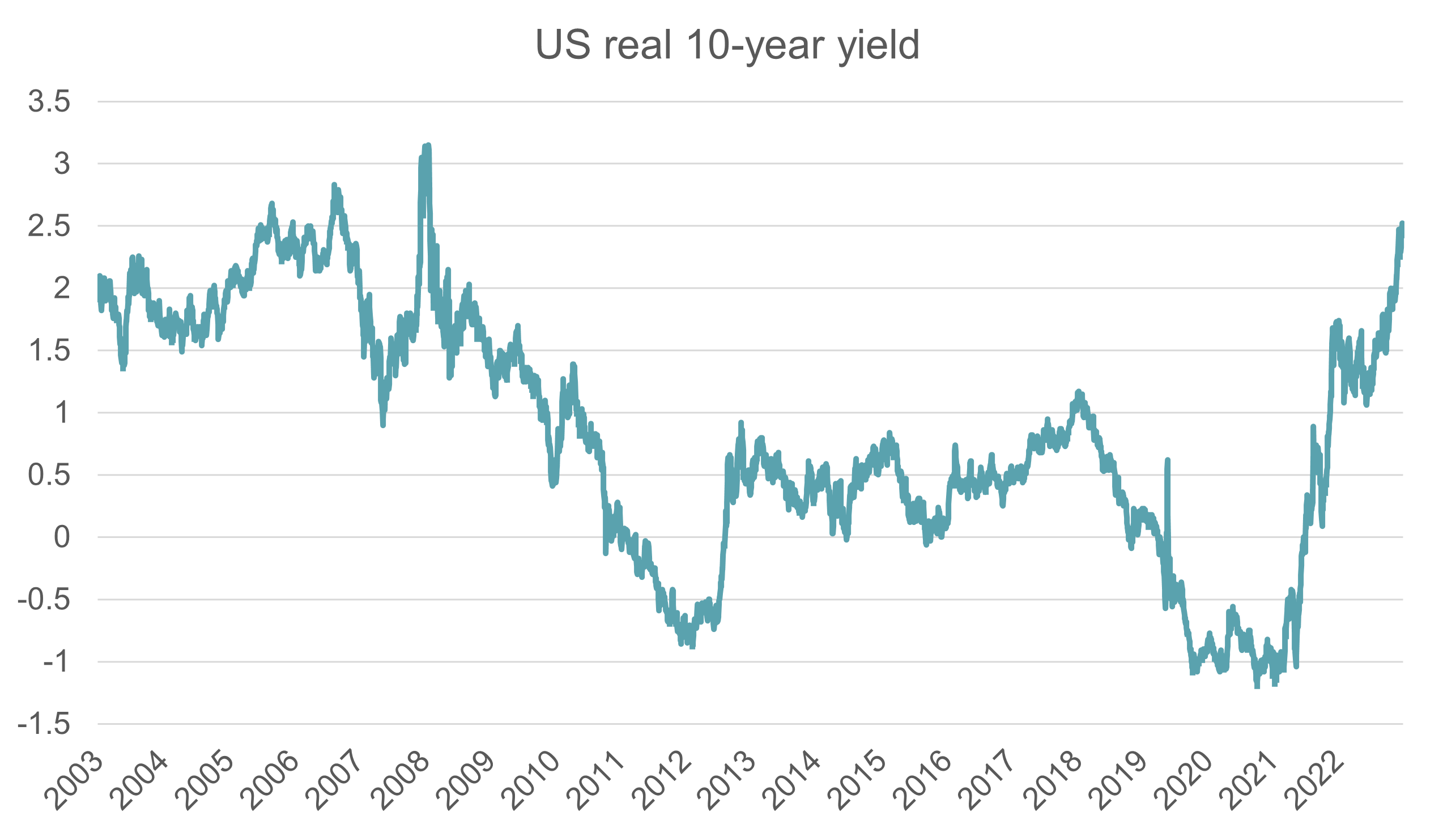

A ‘real’ interest rate is simply the yield on a bond – also known as the nominal yield – minus the market’s inflation expectations. Real yields have garnered attention recently after experiencing a significant rise, returning them to normal historical levels, as shown in the graph below.

Sourced: Bloomberg, 27 October 2023

Why is this relevant for investors?

Valuations

Over the last decade or so, interest rates across the developed world have fallen to historic low levels as central banks kept short-term rates low with the help of quantitative easing, which saw banks buy longer-term bonds to reduce interest rates.

Many investors were confident that rates would remain low and made investment decisions based on this premise. Buying a stock with a 3% free cashflow yield and 3% growth per annum for a total return of 6%, is a logical choice in the context of 1% 10-year nominal yields. However, the margin for error becomes exceedingly narrow when those yields rise to 5%, which is the current outlook in the US.

An example of this can be clearly seen in the performance of the large cap US technology stocks, known as the ‘Magnificent Seven’. The market perception of their pricing power and dominant market positions mean they offer a predictable long-term stream of future earnings. However, despite the strength of their businesses, recently they are being re-evaluated by investors. 5% nominal yields have a risk-free alternative in the US. Despite recent solid earnings reports from the mega-cap tech stocks, they are no longer on an upward trajectory. This, coupled with significant drops in value upon receipt of unfavourable news in the media, mean their values experience significant and sometimes abrupt declines.

Valuations in the rest of the market are already reflecting higher for longer rates. This process is now starting for the ‘Magnificent Seven’ as they begin to compete against one another across verticals, creating a cause for concern for investors. We do not own any shares in the ‘Magnificent Seven’.

Capital allocation

The cost of debt and equity has changed significantly from where it was in the last decade. The ramifications of this change will be significant as fewer projects will be attractive to investors, and buybacks will fall as financing them with expensive debt is not logical. There will also likely be an increase in debt reduction and dividend payments as CEOs and Boards get used to the environment.

In terms of stock picking, we are focused on companies that earn a Return on Incremental Invested Capital (ROIIC) that comfortably covers these higher costs.

Asset allocation

From 2009 to 2021 buying fixed income instruments was the equivalent of buying ‘return-free risk’. This led to an environment of ‘TINA’ (There Is No Alternative) to equities. With the move in rates, we are now back to an environment of receiving ‘risk-free return’ from fixed income.

In summary, the return to a normal interest rate environment will be painful in the short term, but longer term it will bring benefits. The misallocation of capital will be reduced substantially, with value creating projects getting prioritised over financial engineering. Savers will start to see real returns on their deposits, and investors who allocate their resources to well-managed companies trading at attractive valuations will reap attractive returns.

Any views and opinions are those of the Fund Managers, this is not a personal recommendation and does not take into account whether any financial instrument referenced is suitable for any particular investor.

Capital at risk. If you invest in any Gresham House funds, you may lose some or all of the money you invest. The value of your investment may go down as well as up. This investment may be affected by changes in currency exchange rates. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.

The above disclaimer and limitations of liability are applicable to the fullest extent permitted by law, whether in Contract, Statute, Tort (including without limitation, negligence) or otherwise.

Gresham House

Specialist asset management

Gresham House

Specialist asset management