Monthly Monitor - September 2023

Monthly Monitor - September 2023

This month’s round of central bank policy meetings either delivered a pause in interest rate hikes or a clear signal that there will be pause after a move this month. This has reinforced consensus expectations that we are at, or very near, the peak in the current rate cycle. The debate now is moving to what happens next.

Some investment commentators argue that rates will come back down quickly with economic growth slowing and inflation pressures easing. However, another school of thought is that rates will stay higher for longer.

This reflects a view that although inflation is moderating, it remains elevated and sticky, so rates will need to stay high for an extended period in order that they return towards target levels. Furthermore, having worked so hard to get to this point, central bankers will remain cautious to ensure inflation is beaten before easing rates.

An alternative view is that what we are experiencing is a return to normal. But the question is, what does normal look like?

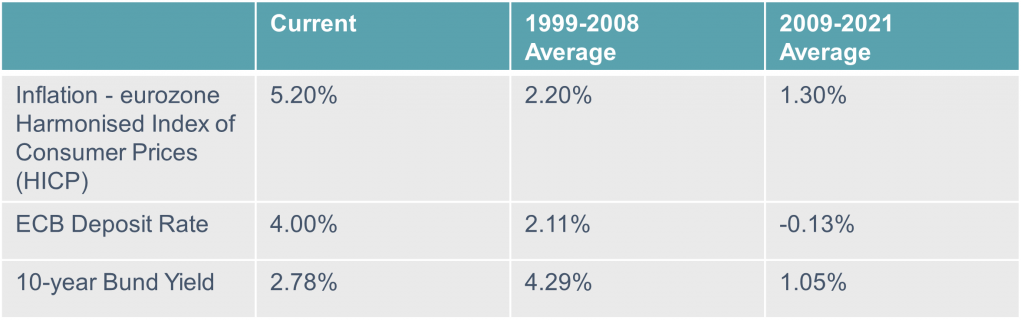

Data sourced from Bloomberg, 26 September 2023

The period following the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) was characterised by low growth and deflationary pressures. During the 13 years from 2009-2021 eurozone inflation averaged 1.3%, well below the ECB target of 2%. The ECB’s response to fight the negative impact of deflation included negative interest rates and a deposit rate averaging -0.13% over that period. Long-term bond yields traded at ultra-low levels, with the yield on the German 10-year Government Bund averaging 1.05% over the 13 years.

The decade following the formation of the euro in 1999 leading up to the GFC was more typical of a “normal” economic environment. During that 1999-2008 decade the average inflation rate in the eurozone was 2.2%, close to target, and the ECB deposit rate averaged 2.1%. The average yield on the 10-year Bund was more elevated at 4.29%.

Inflation in the post-GFC period was not normal. In the current climate, a return to very low levels of inflation is unlikely therefore barring a severe recession or an external shock. This in turn suggests that the return to a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and ultra-low bond yields is also unlikely.

Cyclical issues may result in some easing in interest rates, and the 1999-2008 average of 2.11% suggests there may be some downward scope from the current level of 4.0% if inflation continues to moderate.

Bond yields on the other hand are not above normal levels. The current 10-year Bund yield is 2.78% compared to the 4.29% average of the 1999-2008 period. This has implications for how long duration assets are priced and how long-term liabilities are costed.

After an extended deflationary period of 13 years, it is understandable that the ultra-low bond yields which have persisted may have become normalised for some, but this is a dangerous foundation from which to form a basis for looking at long-term assets and liabilities.

Any views and opinions are those of the Fund Managers, this is not a personal recommendation and does not take into account whether any financial instrument referenced is suitable for any particular investor.

Capital at risk. If you invest in any Gresham House funds, you may lose some or all of the money you invest. The value of your investment may go down as well as up. This investment may be affected by changes in currency exchange rates. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.

The above disclaimer and limitations of liability are applicable to the fullest extent permitted by law, whether in Contract, Statute, Tort (including without limitation, negligence) or otherwise.

Gresham House

Specialist asset management

Gresham House

Specialist asset management